NEWS

Lyric Hi-Fi To Close

April 14, 2021

Julie Mullins

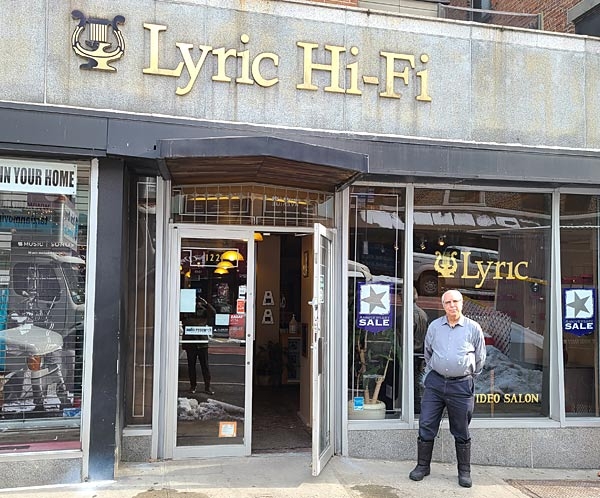

Lenny Bellezza at Lyric Hi-Fi in early February 2021.

New York's Lyric Hi-Fi & Video is one of high-end audio's longest-standing and most legendary institutions. In a recent telephone conversation, Leonard Bellezza, Lyric's owner and president, confirmed what many in this industry have long heard rumored: Lyric is closing.

In 1956, Michael Kakadelis, known as Mike Kay, took a job at a hi-fi store. Kay acquired the business three years later and moved it to Lexington Avenue on the Upper East Side, where it stayed until it closed. Kay was a degreed engineer. He fixed and built audio components (footnote 1).

Lyric had a custom cabinet shop in its basement and assembled complete stereos in credenzas, with turntables by Sherman Fairchild and speaker drivers by Bozak. Lyric also built cabinets for Saul Marantz. The cabinet shop continued into the '90s, and Lyric became an early pioneer of custom install.

Lyric was, arguably, the original high-end store. "Because we were dealing with a very wealthy clientele," Bellezza said, "we were able to sell more upscale products." It wasn't just those well-to-do Upper East Siders, either: As much as 60% of Lyric's business came from international clients, especially Europeans. As Lyric hit its prime, the whole United States had only a couple of high-end dealers equivalent to Lyric: Sound Components of Miami, run by Peter McGrath, and Christopher Hansen Ltd. in Los Angeles. They, too, served an international clientele—from South America and Asia, respectively—alongside locals.

Once a market existed, manufacturers began creating innovative, expensive audio components. Mark Levinson made his first product, the LNP-2 preamp, in his garage and brought it to Lyric, which sold it and ordered more. Lyric raised the profiles of Levinson and Bob Carver, whose Silver Seven amps were voiced on-site, and helped build demand for products from Audio Research, Magnepan, Nelson Pass's Threshold, and MartinLogan.

Lyric's close ties weren't limited to audio companies. They also included the audiophile press: The Absolute Sound's Harry Pearson; Stereophile's J. Gordon Holt. Bellezza was Kay's consigliere and handled politics and egos. "Other 'copycat' dealers opened up," Bellezza said, "because they saw our success and started taking chances on stocking more expensive gear." The high-end scene expanded.

Kay hired Bellezza in 1976, when the latter was just 22. Bellezza had been working part-time at a different audio store while studying engineering and physics at night. He wanted to become a Navy pilot. He also worked as a union usher at Madison Square Garden, Yankee Stadium, Shea Stadium, and Nassau Coliseum. He saw, he told me, "every concert you ever wish you saw."

Bellezza describes Kay as "an emotional Greek" who could be ornery but taught him a lot. "Don't sell them what they want; sell them what they need" was one of Kay's shared mantras.

When Bellezza first visited Lyric, he did so intending to get thrown out, for fun, he told me. Instead, he got hired.

In 1983, Lyric took over the back of a neighboring store. The acoustics were upgraded, including the installation of "floating" concrete floors on top of 3 inches of compressed fiberglass. "Every room was a box within a box," Bellezza said. "Not a single wall was parallel." Mark Levinson and experts from the University of Oslo were involved with the design, Bellezza told me. Engineers Richard (Dick) Sequerra and Mitch Cotter assisted (footnote 2). Sequerra maintained that the concrete needed to be very moist when poured; otherwise it would ring like a bell, Bellezza told me. Cotter maintained just the opposite. When the concrete truck arrived, Cotter told the workers that he "needed to taste the concrete." He found it too moist and refused delivery. The furious concrete workers had to be restrained.

In 1993, Lyric took over the front half of that neighboring business, adding another 800 square feet, for 3600 total—palatial for a Manhattan store. In 2000, Kay bought the space. In 2004, Bellezza and Lyric employee Dan Modoro bought Kay out of the business, but Kay held on to the real estate. In 2018, Modoro retired and Bellezza acquired his share of the business. When Kay passed in 2012, the space passed to Kay's son. It is now up for sale.

New York City is a difficult market for any retail business. Recently, it has been an even harder market for audio, Bellezza said. "New York ranks among cities with the highest per capita income, but in audio it's one of the poorest-performing areas for manufacturers," Bellezza told me.

Bellezza was planning to close Lyric nearly two years ago but decided not to. COVID? It gave Lyric's business an unexpected boost. "Everybody moved out to their vacation homes and upgraded their stereos," Bellezza said.

Pandemic-based business, though, is not sustainable, and longer-term trends are not hopeful, he believes: "High-end audio is not a growing market. Our customers are graying."

Lyric could have done more to attract next-generation clients, he admits, but that ship seems to have sailed: "Nobody young is buying stereo, or very few young people. They all listen to music on their phones, and Sonos in their homes. They don't know what quality is, and they're not interested."

There's an exception though, a special circumstance: Hi-fi runs in families. In a few cases, Bellezza said, he's been providing service to three generations of audiophiles: his main clients, their parents, and their children.

Bellezza has no regrets: "It was a wonderful life."

When the earthquake that was high-end audio shook the American audio scene, Lyric was its epicenter. Now Lyric, like much else, is passing on.

Footnote 1: See Kay's Stereophile obituary here.

Footnote 2: Cotter and Sequerra both had a hand in the design of the legendary Marantz 10B tuner, among their many contributions to hi-fi.

Read More:

https://www.stereophile.com/content/lyrical-denouement

then "Add to Home Screen"

then "Add to Home Screen"