NEWS

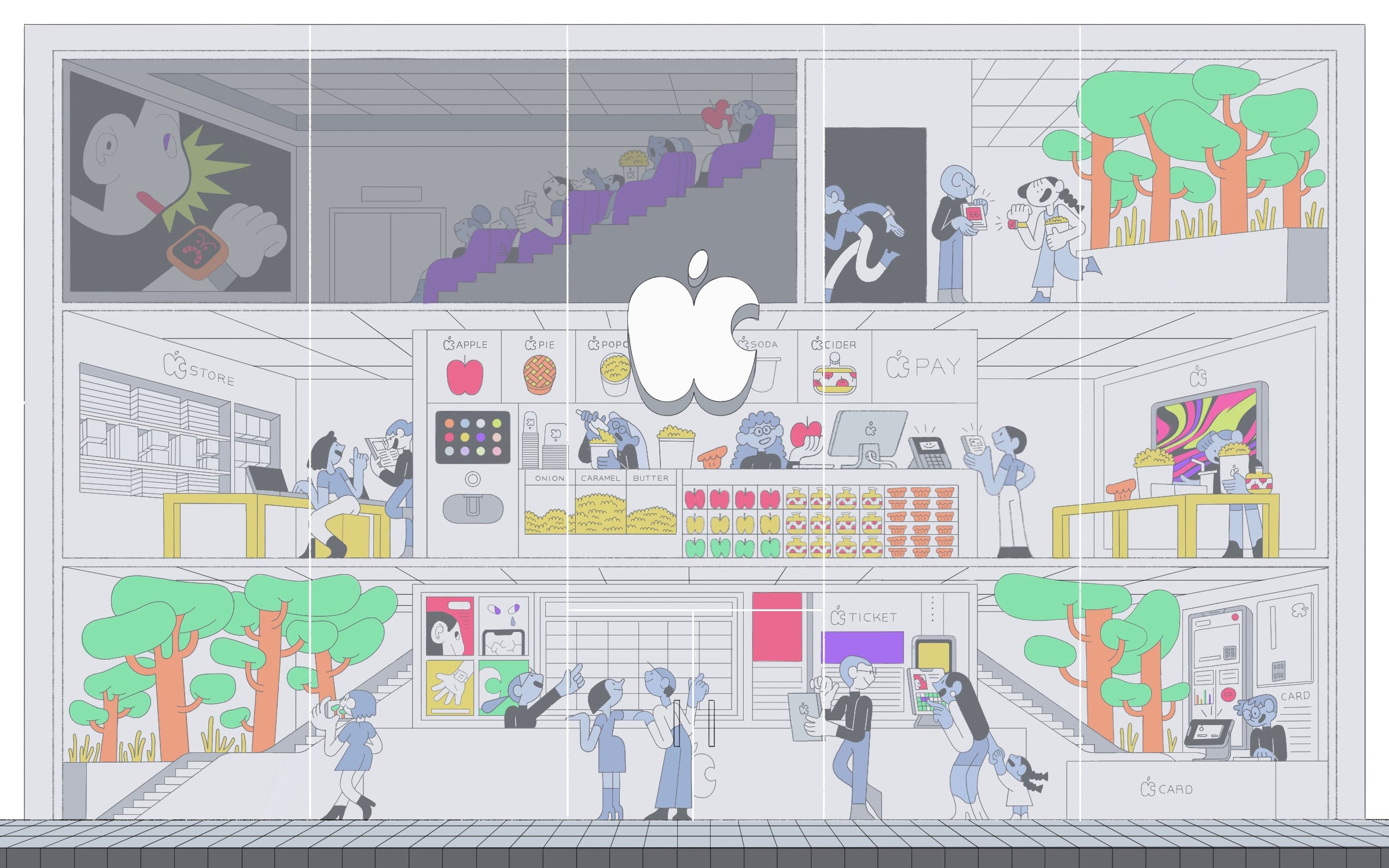

The Future of Movie Theaters Might Look a Lot Like an Apple Store

May 22, 2020

Eric Ravenscraft

Illustration: Nan Lee

It’s no big secret that the movie theater industry is facing an existential crisis, with serious challenges coming from streaming platforms developed by technology giants like Apple, Netflix, and Amazon, and now a pandemic that’s forced cinemas to shutter around the globe. Weighing the future of movie theaters has become a favorite guessing game for media analysts. Last Friday, the New York Times asked: “Movie Theaters Are on the Brink. Can Wine and Cheese Save Them?”

Maybe not. But there’s reason to believe that the very tech companies threatening the industry could breathe new life into movie theaters.

Last week, rumors circulated that Amazon is interested in acquiring AMC, the largest theater chain in the United States. The news caused a sharp spike in AMC’s stock price. The company has had a rough year: The chain lost money in 2019, despite multiple billion-dollar tentpole releases such as Avengers: Endgame, The Lion King, and Frozen 2. And that was before the coronavirus pandemic shut down theaters worldwide. Now, some analysts have speculated that the company might file for bankruptcy. While the theater chain denied the speculation, it raised $500 million in additional debt to weather the current crisis.

It’s not hard to imagine a merger between a theater chain and a big tech company. Picture stadium seating for original Apple movies like Greyhound at one of the company’s “Town Square” stores, right next to the iPad displays. Or an Amazon theater with a pick-up locker in the lobby and a Whole Foods-branded concession stand. When we emerge from quarantine, there’s a real possibility that the neighborhood multiplex will have a brand in common with the company that delivers your odds and ends.

If Apple, Netflix, or Amazon owned a theater chain, the company would make money no matter where consumers decide to watch movies.

Stephan Paternot, a film producer and co-founder of independent film financing marketplace Slated, thinks that movie theaters could naturally complement a large tech company’s streaming platform.

“Even though everyone’s going on and on about ‘streaming is the future,’ …everyone still needs to get out of the house,” Paternot tells OneZero. And if Apple, Netflix, or Amazon owned a theater chain, the company would make money no matter where consumers decide to watch movies.

Amazon, for example, could apply its Whole Foods model to a theater chain, turning the brick-and-mortar locations into extensions of its online business. An Amazon Prime subscription that includes trips to movie theaters — similar to AMC’s A-List subscription — could complement its streaming service. As Paternot explained, “If Amazon was going to buy AMC, it’s an opportunity for them to sell their most popular Whole Foods snacks. And then to maybe charge you another hundred dollars a year for Prime, and you get all-you-can-eat [films] at home and at the theater.”

Sure, there could be bumps in the road: Amazon’s integration with Whole Foods has certainly hit a couple. Workers reported deteriorating working conditions, and the number of new customers to the stores decreased in early 2019 compared to the year prior. Whole Foods also cut ties with Instacart, promoting Amazon’s own delivery service instead, which is obviously good for Amazon itself, but results in fewer choices of delivery options for customers compared to competing grocery chains.

An Amazon merger with a theater chain would be exactly the kind of vertical integration — and loss of consumer choice — that the 1948 Paramount Consent Decrees were meant to combat in the film industry. The decrees prevented certain major studios from owning theaters and showing only their own movies, excluding not just competitors, but indie filmmakers as well. If Apple were to build its own Apple TV+ theater, it might choose not to show Netflix movies inside. After all, this is the company that doesn’t allow mention of “other mobile platforms” on its app store.

But there are plenty of loopholes. Those decrees govern legacy players and don’t account for new companies in the industry. Disney wasn’t a major studio in 1948, and tech companies like Amazon, Apple, and Netflix didn’t exist yet, so the consent decrees don’t govern them, and it’s unclear whether they would also be in violation of the law by vertically integrating. Meanwhile, the Department of Justice under the Trump administration is pursuing an end to the decrees anyway, so it’s possible they would not be prosecuted in the same way, and whatever rules exist right now may not for long.

There is already precedent for tech companies (and Disney) moving into the theater business. Netflix signed a long-term lease on the single-screen Paris Theater in Manhattan in late 2019, where it can exhibit its own films like The Irishman and Marriage Story. The venue gives Netflix a historic outlet that can lend prestige to its films. And last year, it was reported that Netflix was in talks to acquire the famous Egyptian Theater in Hollywood.

This is also a maneuver on Netflix’s part to sidestep strict “windowing” rules that major theater chains use to force studios to grant an exclusivity period before films appear on streaming platforms or to rent. These rules are why Rise of Skywalker didn’t appear on Disney+ until earlier this month despite a December theatrical release.

The race is on to find out who will be the first to do everything: Blockbuster theatrical releases, prestige award film runs, and streaming rentals and subscriptions.

But this isn’t just about dollars and cents. The Academy Awards require any film considered for its awards to screen for at least one week in a commercial theater in Los Angeles County, where the Egyptian is located. Owning the Egyptian Theater would allow Netflix to screen its own movies and qualify for awards, regardless of whether other theaters choose to show its films. (This rule was recently relaxed in light of theater closures due to the coronavirus.)

Theater acquisitions are a prestige play for tech companies that, for all their money and power, are still working to gain standing alongside studio juggernauts like Disney and Warner Bros in the eyes of critics and the film industry they’re attempting to court. In some sense, the two industries are coming for each others’ most valuable assets: Disney owns blockbuster films in theaters, and now it’s aiming to catch up to Netflix’s streaming subscribers with Disney+. Meanwhile, Netflix dominates in streaming, but the company — alongside Amazon and even Apple — is striving to gain legitimacy in theaters.

The race is on to find out who will be the first to do everything: Blockbuster theatrical releases, prestige award film runs, and streaming rentals and subscriptions. And there’s good reason to believe each of these will continue to be standalone sections of the movie industry.

Blockbuster films are unlikely to head to streaming platforms exclusively because there’s simply too much money to be made from event films. As boxoffice.com analyst Shawn Robbins told CNN, tentpole movies like Mulan have “too much global potential to skip a traditional release in theaters.” If that weren’t the case, Mulan would be on Disney+ already.

“Streaming” is also used as a shorthand for multiple types of distribution, not all of which are equal. Disney+ is an all-you-can-eat subscription, and doesn’t yet offer the kind of high-priced streaming rentals that brought Universal impressive returns for Trolls: World Tour. Even if Disney could bring in a billion dollars from a tentpole release — and that’s very unlikely to be the case — it would be more complicated than slapping it on Disney+. For now, even Disney still relies on Amazon in that regard.

According to Paternot, the scale of blockbuster films has already given major studios a de facto oligopoly over theaters anyway. “Independent makers right now, from sheer competition from tentpoles, have been elbowed out of the way,” he said. While a small fraction of the independent films his platform has helped find funding see theatrical releases, most success stories end up on streaming platforms. Viewers are simply more willing to take a chance on an indie movie from their couch on Netflix, rather than when it’s competing for theater space with Avengers: Endgame.

As indie media shifts to subscriptions, theaters are increasingly positioned as event destinations. This shift could contribute to the theme park-ification of movie theaters which would only make them more attractive to tech and studio giants.

For as important as merchandise is to franchises like Avengers or Star Wars, for example, that merchandise is starkly absent from the theaters where those movies are shown. Amazon could feasibly sell overpriced action figures — shipped in from the nearest Amazon warehouse — in theaters just as easily as it sells overpriced popcorn. Even more so if a studio like Disney were to buy a theater chain and stock it the copious merch that already fills its Disney Stores.

The result would make visiting a movie theater feel less like going to a multiplex and more like a trip to Disney World.

However, it’s unclear how smaller theater chains like Landmark would fare in a world where major theaters are owned by tech giants or studios. Right now, studios have no choice but to put their tentpoles on as many screens as possible, but if they owned their own chains, that might leave independent theaters out in the cold.

With no merchandise to sell, no grocery store to provide snacks from, no film studio to promote, and no streaming platform to tie in with, an independent movie theater is just a room with a really nice screen and a comfy chair.

And you already have one of those at home.

Read More:

https://onezero.medium.com/the-future-of-movie-theaters-might-look-a-lot-like-an-apple-store-185c941d02a5

then "Add to Home Screen"

then "Add to Home Screen"